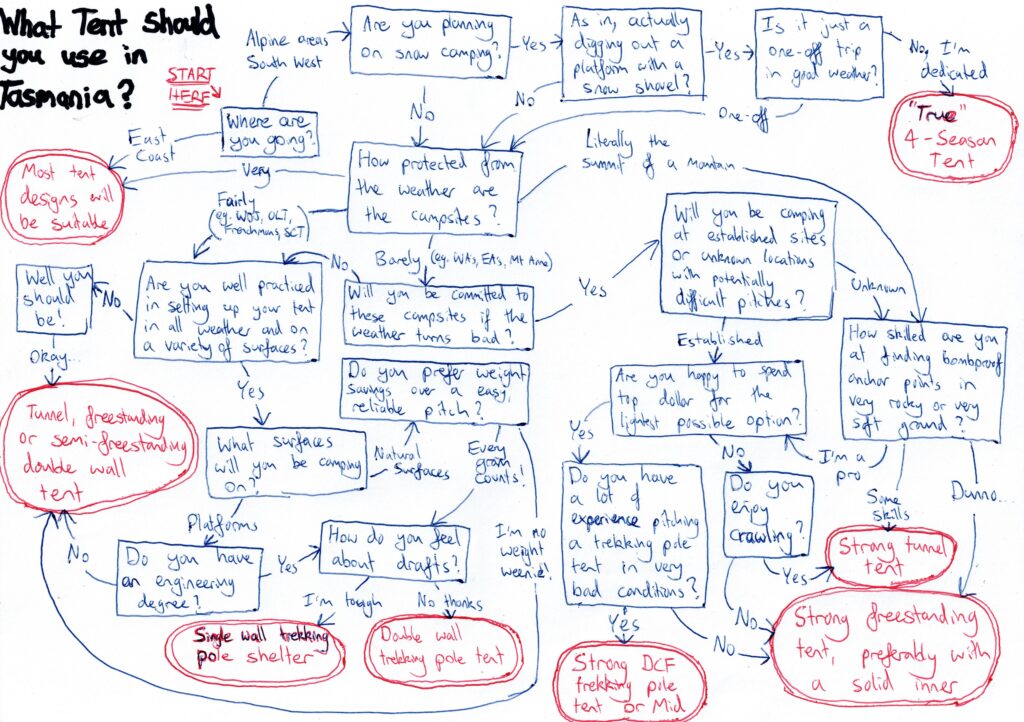

Tent Categories Explained

Conventional Double Wall Tents

These tents have a waterproof outer layer (fly) combined with an inner (either a solid fabric or a flyscreen) that has a waterproof floor.

The fly will usually made of siliconized nylon or polyester which can stretch slightly. Recently some tents in this category have started using a Dyneema Composite Fabric (DCF) or equivalent, which is an extremely light material with high tensile strength and no stretch.

The inner layer keeps out insects and will increase the temperature inside the tent (particularly if it’s a solid inner). It also provides a barrier against the inside of the fly which often gets wet due to condensation.

The poles will be either carbon fiber or a lightweight alloy, and can vary in terms of strength and stiffness.

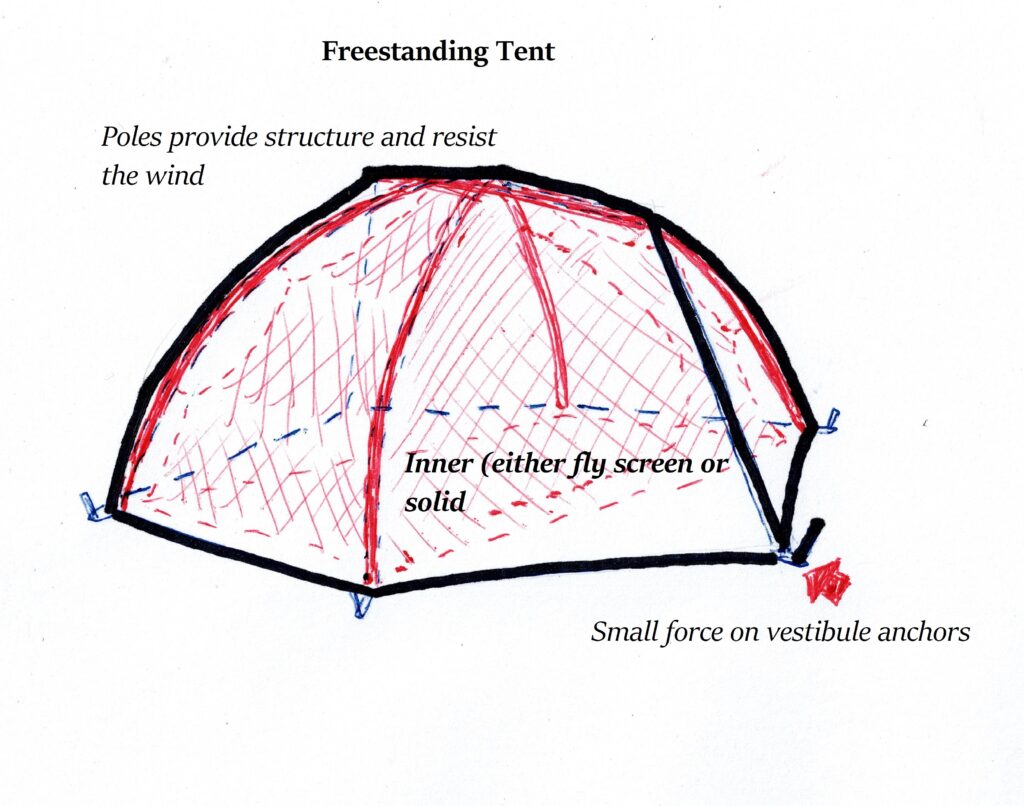

A freestanding tent has multiple poles that cross over each other in such as way that it can be pitched without any pegs (although often the vestibules need to be pegged out to be functional). The design uses the tension of the bent poles to provide structure. Freestanding tents have the advantage of being easy to pitch and not overly reliant on strong anchor points. Freestanding tents vary enormously in both design, stability and strength.

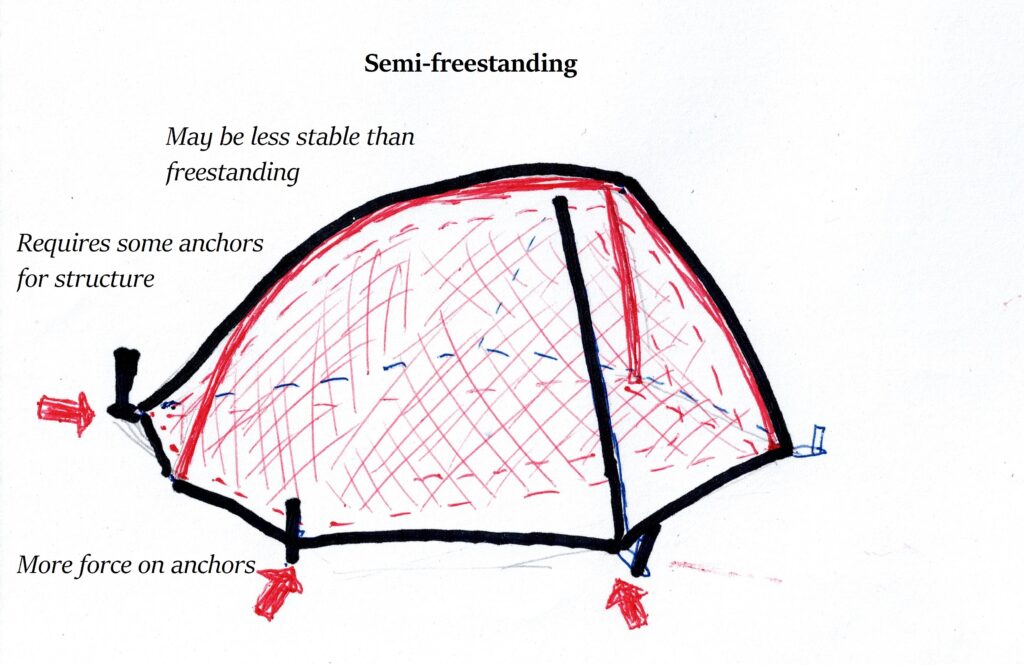

A semi-freestanding tent will have a similar design to a freestanding tents but may require some anchor points for structure. Some tents (particularly 4-season tents) will be essentially freestanding, but may have a large vestibule with an arch pole that requires anchors for tension.

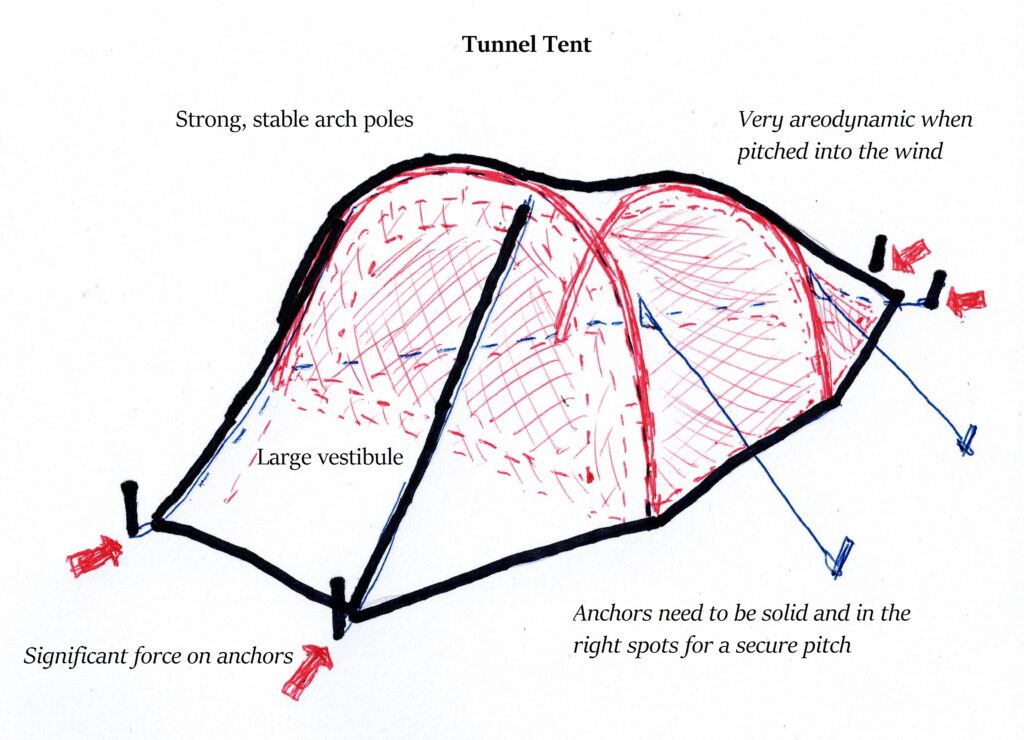

These consist of a series of arched poles (usually two or three) that require lengthways tension provided by anchors. These tents can be very wind resistant, with their low aerodynamic shape and stable arches, but will generally need to be pitched parallel to the wind direction with strong anchor points to perform well. Unlike freestanding tents, the tension of the fly is dependent on the placement of the anchors, meaning that a misplaced anchor can make for a saggy, billowy tent.

Trekking Pole Shelters

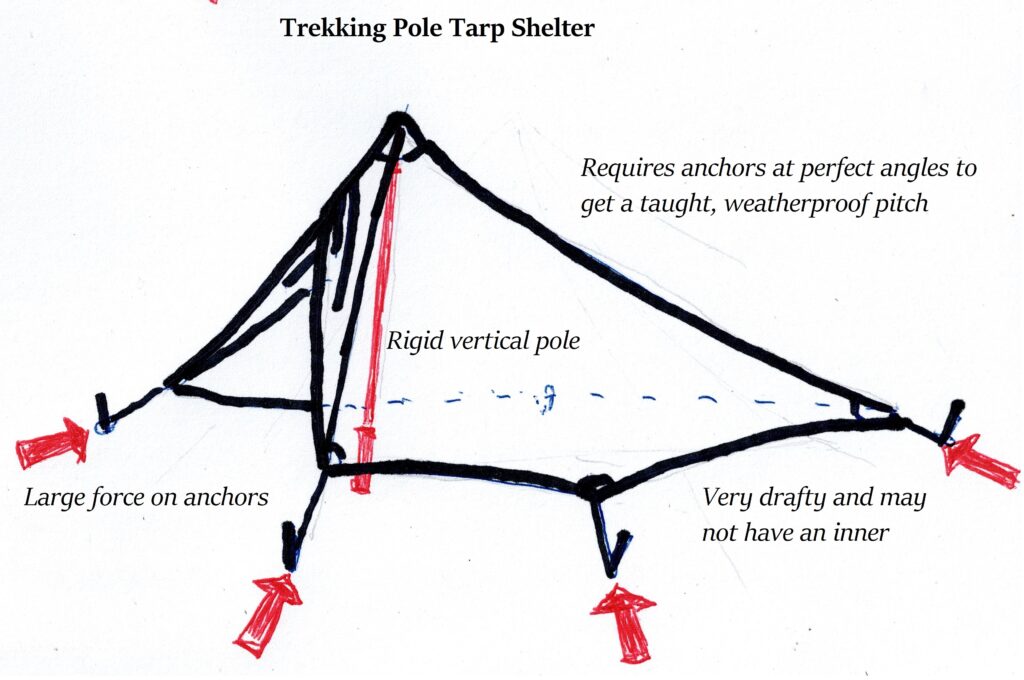

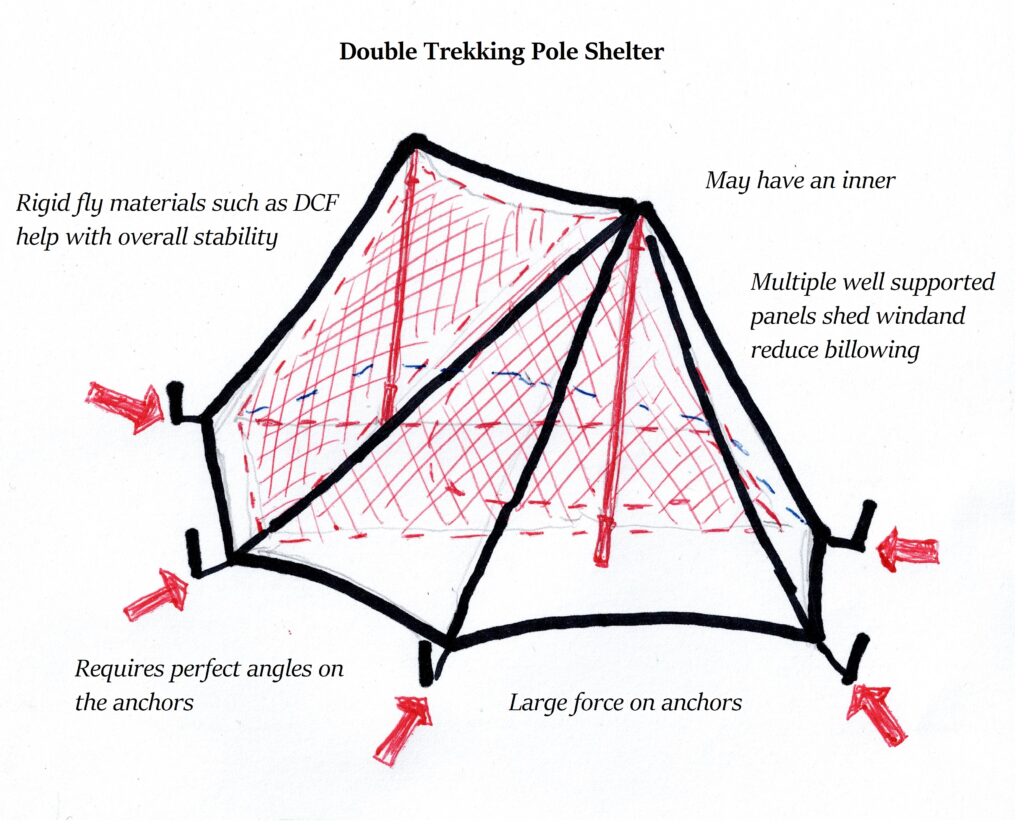

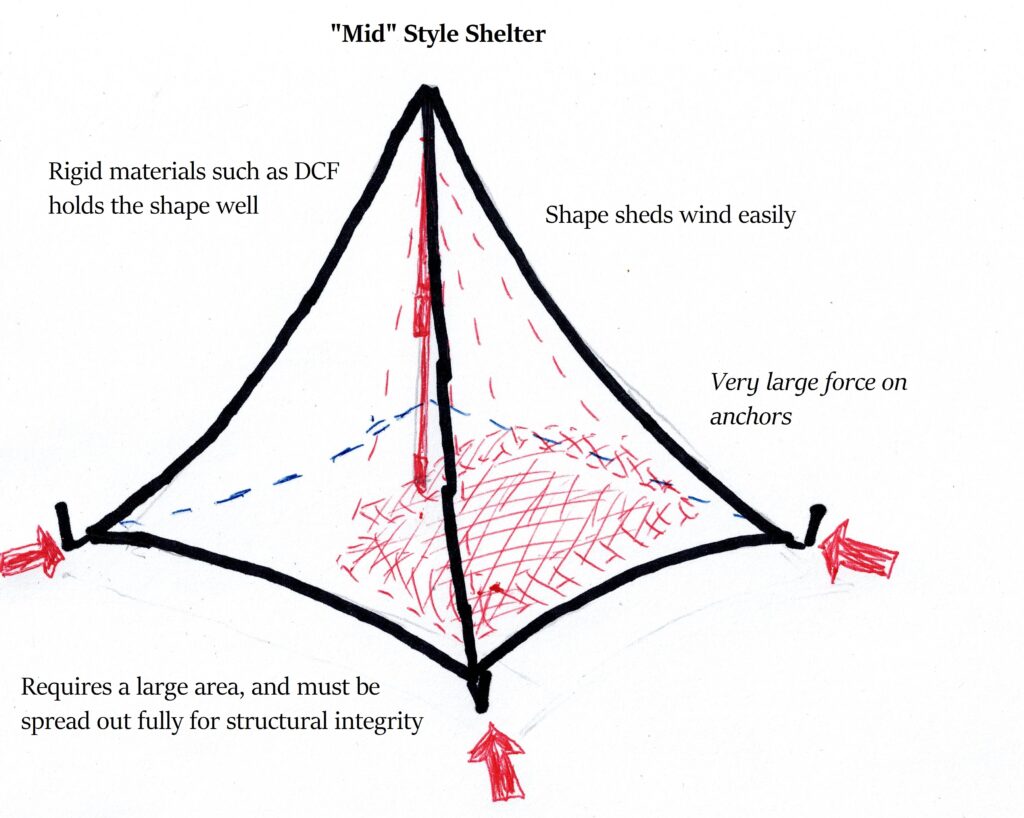

This category refers to a wide range of tents and shelters that use upright trekking poles (or other rigid poles) instead of conventional tent poles. While trekking poles are very strong, the shelter’s structure will be entirely dependent on the anchors. As a result, these anchors can experience a lot of force in high winds. Pitching trekking pole shelters also requires skill and experience as the position of the anchor placements need to be perfect in order to achieve a taught, weatherproof pitch. Rigid materials such as DCF can make for a stronger shelter, as the fly will not billow inwards as it would with a stretchy fabric. However, the lack of stretch does make the position of the anchors even more critical.

These are essentially small, shaped tarps that are held up by a single pole. While some may have a basic inner, they are very drafty and can be difficult to manage during bad weather in exposed alpine campsites.

These tents use two trekking poles for structure and will have either a basic flyscreen connecting to a floor, or a full solid inner. They shed the wind well thanks to their many well-supported panels, and they can be a very stable and weatherproof option in exposed locations. However, as with all shelters in this category, their strength is very dependent on the quality of the pitch and the strength on the anchors.

Pyramid Tents or “Mids” are a large single-skin shelter designed for multiple people. They have a high central post (either multiple trekking poles lashed together or a dedicated pole) and four to six anchor points. They can be combined with an interior flyscreen/floor or individual bivvy bags. While the shape does effectively shed the wind, the size of the panels and the relatively few anchor points mean that each anchor can experience enormous forces. The large size also presents a challenge in tight campsites, as it will need to be fully stretched out in order to have structural integrity.

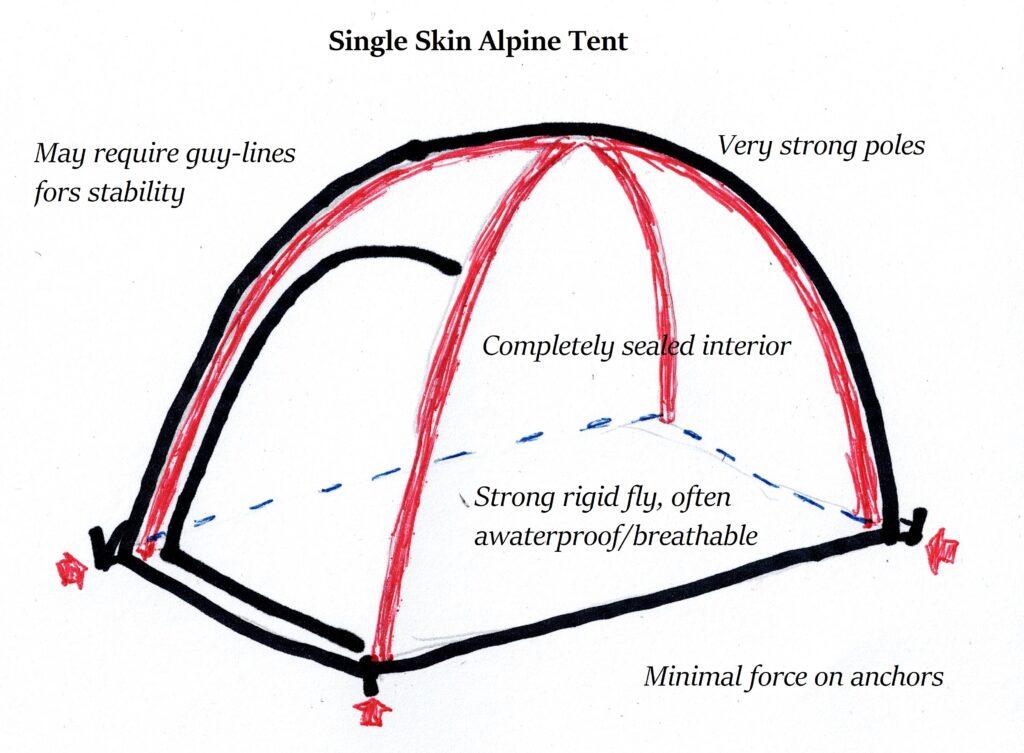

Single Skin Alpine Tents:

These are basic freestanding tents with no inner and a fully enclosed fly/floor. The fly is often made of a waterproof/breathable material (such as Gore-Tex) and can be very strong with virtually no stretch. The poles are also generally stiffer and stronger than the poles in a regular freestanding tent. While they can be incredibly weatherproof for their weight, the lack of ventilation and enclosed nature means condensation is a huge issue, particularly in humid climates like Tasmania.

Do you need a 4-season tent in Tasmania?

The distinction between 3 and 4 season tents can be confusing and is often quite misleading. Unlike sleeping bags or other equipment with an objective rating, the “season” rating of the tent is nothing more than an untested claim by the manufacturer.

A true 4-season tent is one which is intended primarily for snow-camping. It should have features such as:

-A fly that extends down to the ground (often with a “skirt” which can be buried) to seal in the warm air and minimize the entry of windblown snow.

-A structure that will resist collapse if it gets buried in snow.

-A inner that is completely solid and stops airflow as well as the entry of light spindrift.

-A large vestibule to help keep the inner snow free.

-Multiple guy lines for stability.

While a 4-season tents should also be very strong, there is no guarantee that a tent marketed as 4-season is going to perform better in the wind than a 3-season tent.

When it comes to Tasmanian conditions, the features of a 4-season tent are only really warranted for dedicated snow camping. While it’s true that snow can occur at any time of year, the conditions that a 4-season tent is designed for (deep snow pack, windblown spindrift, heavy snow loading) are so rare they usually have to be sought out, and even if they are encountered a strong 3-season tent should manage.

However, those who are doing extended, off-track trips where the weather can’t be predicted and the only campsites are extremely exposed ridgetops, may wish to get the strongest, most reliable tent possible for peace of mind. These will usually be 4-season tents designed for mountaineering or polar travel, which will have significant drawbacks in terms of weight and condensation. For the majority of walkers, these kind of tents are inappropriate.

What makes a tent weatherproof?

Assessing the strength, stability and reliability of a tent before you buy it can be a challenging task. Do as much research as possible, but be wary of reviews that test in environments and conditions that don’t relate to what you’ll be facing. For alpine Tasmanian conditions, some key attributes to look for are:

– Overall stability: If you get to see the tent properly set up, try and gauge how “solid” the tent feels. Do the poles bend and sway easily with a little force? Are there large unsupported panels that can easily be pushed inward? Is there a lot of movement between the poles and the fly?

-Water ingress: Can the fly easily billow inwards and get the inner wet? Are there large gaps between the fly and the ground that wind-driven rain could enter? Can moisture pool anywhere on the fly?

-Guy-lines: For freestanding and tunnel tents, multiple guy-lines will help with stability. Generally, guy-lines aren’t as useful for trekking pole tents.

-Durability: Are the components that will experience high loads (eg. pole attachment points, anchor connections) reinforced and solid feeling? If there are conventional tent poles, do they feel stiff, or flimsy? While poles made of carbon have very high strength to weight ratios, they can sometimes be brittle and less reliable than alloy poles. The durability of the fly material is difficult to assess by feel, as many extremely light fabrics have high tear resistance and tensile strength, while cheaper, heavier fabrics may actually be weaker.

-Inner: Some relatively strong tents (particularly trekking pole tents) might only have a flyscreen inner, or no separate inner at all. While this won’t affect its stability, the interior of the tent may be colder and damper in bad weather, particularly if it’s airy and well-ventilated. This set-up may work for some users, but unless you have a lot of experience, it would be advisable to go with a solid or partially-solid inner for extended trips in exposed, alpine environments.

Takeaways:

When venturing into Tasmania’s South-West and alpine regions, the brutality of the weather and the nature of the campsites present some unique challenges for tents. Here are my key points:

-While strong tents are required for the Tasmanian alpine, true 4-season tents are only really necessary for snow-camping.

– Many popular walks have tent platforms. These have limited anchor points and may require creativity to get a good pitch (unless you have a freestanding tent).

-Resistance to strong wind is the most important feature for remote trips in exposed alpine environments.

-Trekking pole tents and Mids are appropriate for Tasmania, even for committing, exposed trips. However, there are some major caveats: 1) Not all trekking pole tents are the same, and some are totally inappropriate. 2) They are a specialist tool for skilled and experienced users, and their strength is entirely dependent on the quality of the pitch. 3) You must know what kind of surface you’ll be pitching on (platforms, soft ground, bedrock) and be skilled enough to find bombproof anchor points.

-Freestanding tents are probably the most versatile and reliable choice, particularly for beginners.

-While single skin alpine tents are strong, they have significant drawbacks that make them a less practical choice for Tasmania.

Leave A Comment