(For a general overview of shoe performance in technical terrain, and definitions of terms and categories, see https://wildernessexpeditions.net.au/footwear-in-technical-terrain/)

Footwear choice is a hotly debated and surprisingly polarizing topic. Listening to the multitude of opinions out there can be bewildering and unhelpful. I think it’s useful to narrow the problem down to a few key questions:

- What are you used to?

- How do you like to move?

- What kind of terrain will you be moving through?

What Are You Used To?

Familiarity is important. While I encourage everyone to branch out and experiment with different kinds of footwear, if you’re going out into the wilderness (particularly for something long and remote) stick to what you know. Choose a style that you’ve used previously and feel secure and comfortable in, and avoid feeling pressured to switch to something different just because someone told you that you should. If you’re just starting out, or venturing into a new kind of terrain, make sure you have put plenty of k’s in whatever you will be wearing! Even if your new shoes don’t require a break in period, getting familiar with how they feel on a variety of terrain types is incredibly valuable. Having said that, be wary of taking that trusty pair of boots that have been with you for decades. If you still use them regularly, they should be okay, but if they’ve been sitting in a cupboard for a few years, the process of hydrolysis can cause a catastrophic failure of the outsole, even if they look pristine!

How Do You Move?

Your individual biomechanics, skill, strength and movement style should influence what you use. Do you like to feel what’s beneath your feet, or would you prefer to have some armor plating between you and the ground? Do you like to hop from rock to rock, articulating your foot to match each new slope, or do you like to move slowly and steadily, planting your boots securely between the rocks? How often do you find yourself stubbing a toe, or catching the side of your foot on something sharp? Do you like cushioning and a smooth rolling transition, or is a firm, flat and direct connection to the ground more your thing? Will you be walking, running or doing something in between?

Normally the category of trip (ie. day walk, multiday with a heavy pack, run) tends to dictate the kind of footwear that gets recommended. While it’s true that a heavy pack will slow your cadence down, increase the forces experienced by the foot and make an ankle roll more damaging, I think that the personal factors mentioned above are still more relevant to footwear choice. Getting this awareness of personal preferences takes time and experimentation, and I would suggest for beginners to start with something in the middle and be skeptical of anyone who treats their preferences as gospel truth.

Where are You Going?

I created 4 levels of Tasmanian terrain. These do not reflect the overall difficulties of these routes, but rather their level of technicality and the nature of the track (or lack thereof). For each level I’ve made some suggestions of the kinds of footwear that might work for you, and some considerations specific to each.

Level 1:

Smooth, wide, well-built paths.

Examples: Three Capes Track, Cape Raoul, some tracks on kunanyi/Mt Wellington, Wineglass Bay

Recommendations:

Pretty much anything that you are comfortable walking/running in will work for these. While there will be occasional uneven footing, loose gravel and rock work, there is no need for highly technical footwear. To reduce the impact of the hard surfaces you may appreciate the rocker and softness of max-cushioned trail runners, or their hiking boot counterparts. Stiffer boots may feel a little clunky and uncomfortable, and while they are still appropriate, it’s probably overkill for most people. If you are doing a multi-day walk such as the Three Capes and prefer walking in low-cut shoe, ignore those who insist that you must wear a high-cut boot.

Level 2:

Well-formed and maintained tracks, but with varied natural surfaces. Plenty of roots, rocks and some mud. There may be sections where there are few flat places to step, and lots of slippery surfaces and awkward angles. Often there will be steep climbs and descents with big steps.

Examples: Walls of Jerusalem, Freycinet Circuit, Overland Track, Tarn Shelf, day walks around Cradle Mountain, Hartz Peak

Recommendations:

While these tracks are relatively mild by Tasmanian standards, the roughness of the terrain often surprises people who are used to the manicured trails found elsewhere in the world. Comfort still matters, but it is important that the footwear you choose is going to give you confidence on the constantly uneven ground.

High-cut stiff boots are a common option, but they shouldn’t be considered a necessity. If they are a good fit and are well broken in, they can be very comfortable and may reduce some of the stress experience by the foot on uneven ground. However, their chunkiness and stiffness can actually be an issue for those who are not used to them, and rather than providing true ankle support they can cause additional instabilities.

Light mid-cut boots, walking shoes or trail runners are probably the most versatile options. Regardless of the specific style, make sure that the fit is snug and securely holds your foot in place. Too much sloppiness in the uppers (particularly when combined with a stiffer sole) can mean that the shoes feel a bit disconnected from your feet.

Some of these shoes will have a waterproof membrane. This can be a nice feature to have (and helps motivate you to walk directly through puddles!), however it is not a guarantee of dry feet. In very wet conditions water inevitably seems to find a way in (even when gaiters are used) and often the membrane will degrade over time and begin to leak.

In very cold, wet conditions the membrane can be more useful as it tends to keep your feet warmer (even if they do get wet). Waterproof socks can provide a similar insulating effect if your footwear does not have a membrane.

Be wary of highly cushioned, high stack shoes. While they can be an option those who are used to using them in this kind of terrain, the mushiness of the midsole and the inherent instability of a higher stack may make them feel a little precarious when stepping on off-camber rocks and roots. Many higher stack shoes will have a wider platform to counteract this effect, but this can make the shoe feel clumsy, imprecise and prone to catching on obstacles.

Very minimalist footwear is a less common choice, probably due to the lack of protection from the sharp rocks underfoot. Having said that, the Overland has been walked completely barefoot before!

In terms of traction, most trail-specific outsoles should be fine. Very shallow lugs (less than 3mm) will struggle a bit in slippery mud, but they will still be adequate.

Level 3:

Very rugged tracks. Awkward clambering over rocks and boulders of all sizes, tangles of roots and branches, deep mud, scrambling up rock slabs.

Examples: Frenchmans Cap, Western and Eastern Arthurs, South Coast Track, Mt Anne Circuit, Mt Murchison, Southern Ranges, Overland Track side trips and countless other alpine peaks.

Recommendations:

This is the kind of terrain that gives the Tasmanian wilderness its gnarly reputation. Traditionally, these tracks have been considered to be very much boot territory, however a variety of styles can still work, depending on personal preference.

Despite the alpine nature of these tracks, mountaineering boots are not usually the best choice. Mountaineering boots are designed for the kind of alpine terrain seen elsewhere in the world (think triangular peaks with broad, steep faces and a permanent snow pack). They are designed to provide a comfortable platform to “edge” (either on firm snow, scree or a rock face) for a long period of time, often with crampons attached. Tasmanian alpine terrain, while often steep, is much more uneven and includes boulders, tree roots, alpine vegetation and slippery rock slabs. The rigid soles and inflexible ankles of mountaineering boots have a hard time adjusting to these awkward angles. In true winter conditions (ie. deep, firm, consolidated snow) mountaineering boots may be appropriate, but these conditions are so rare they usually have to be sought out.

While high-cut walking boots share characteristics with mountaineering boots, they are generally more flexible and versatile. They will still prioritize edging over smearing, but this can be used effectively by standing on small footholds or wedging them securely in gaps and corners. The protection offered by solid boots is probably their most important feature in this context.

Lighter boots will have some of these advantages, but to a lesser extent. However, be careful with the style you choose, as many boots in this category may be designed more for comfort than performance on technical terrain. Avoid loose fitting, chunky, excessively rockered and highly cushioned boots. These will have the clumsiness of heavier boots, but none of their advantages in terms stability, support or edging ability. Look for boots with structured and protective uppers, firm midsoles, and outsoles with deep lugs and rigid, sharp edges.

Approach shoes will have similar characteristics to more technical boots, but with superior edging ability and friction on rock. Be careful with more aggressive, climbing focused styles as they may be uncomfortably snug in the toe box, and unsuited to longer distances.

Trail runners are increasingly being seen as a viable option. Instead of focusing on support, protection and edging, these shoes prioritize mobility and being able to precisely adjust to footholds. They are a great option for those who want to move quickly and nimbly. The lack of structure and support will mean that the foot is much more engaged with every step, which (depending on your experience and physical conditioning) can be either a positive or a negative. The tracks in this category are often very boggy, and wet feet are an inevitability with trail runners. However, they will drain and dry quickly.

As mentioned previously, be wary about high stack, max cushioned shoes, particularly the carbon plated trail “supershoes” that have emerged in recent years.

Very minimalist trail runners and barefoot style shoes are a more extreme, but potentially worthwhile option. This approach emphasizes the “smearing” style of foot placement, and would be particularly useful when hopping between the ubiquitous boulders. However, as with most trail runners, protection and durability will be the big weakness here. Skilled footwork is a must, as repeated slips, missteps and stumbles will wreak havoc on your feet (and your shoes) over the course of a long trip.

Traction is obviously very important in this kind of terrain, especially when a failure of traction can result in you plunging head first into a boulder-field with 20kg on your back. Luckily Tasmania’s main rock types generally have quite good friction, especially dolerite. However, when lichen, dirt and moisture is involved they can become quite treacherous. The outsole material will make a considerable difference to performance on rock, however it is still secondary to how effectively the shoe/boot (and the foot controlling it) can exploit the friction available.

While the muddiness of the Tasmanian wilderness is well known, it probably shouldn’t factor too heavily into choice of outsole. In very deep mudholes where sinking to your thighs (or beyond!) is a possibility, it doesn’t really matter what’s on your feet. In the slippery ruts and mud steps common to alpine and buttongrass areas, stiff boots will probably have an advantage with their ability to edge into the mud. Mud specific trail runners with a very aggressive tread may fare better in these situations, but the difference will be slight, and other factors such as hard-ground traction may make a more all-round lug pattern more appealing. Regardless, a lug depth of 4mm or more will probably be appreciated.

Level 4:

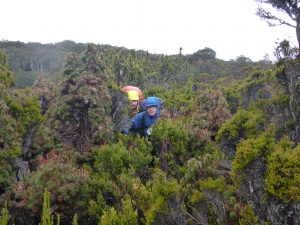

Off-track. This includes a huge variety of terrain types and difficulties, but at the harder end of the spectrum you can expect brutal scrub, unstable footing, and clambering over all manner of rock and vegetation. Often the ground you are stepping on will not even be visible.

Examples: Anywhere is the Tasmanian wilderness!

Recommendations:

Hefty boots are the standard choice, both for their protection and their stability on soft, unsteady ground. High cut full-grain leather boots are generally favoured, as they have greater durability than their synthetic counterparts. Look for boots with generous rands and minimal seams on the uppers. Scrub and rock tend to catch on seams and abrade them over time (this process is aided by Tasmania’s slightly acidic mud).

Lighter boots are still an option, but you need to be realistic about their longevity in this kind of terrain.

Trail runners are definitely a rarer sight on the harder off-track routes, but they are still worth considering, particularly if you want to move quickly. The big drawback is their lack of protection, especially around the ankles. As with the level 3 terrain, the sensitivity and precision afforded by lighter shoes makes for a very different biomechanical experience. It’s worth noting that back in the 70’s and 80’s there were a group of walkers from NSW who pioneered some of Tassie’s hardest routes exclusively in Dunlop Volleys! Although apparently, they got spare pairs flown in with their food drops. The durability of trail runners is something that should be carefully considered, especially on extended trips where torn uppers could become a trip-ending issue. Many trail running brands have started making uppers out of harder wearing materials such as Matryx (aramid based yarns), TPU and Dyneema. This is a huge advantage if you are looking to take trail runners into this kind of terrain!

Leave A Comment